In summer of 2020, I provided a personal security and privacy lecture to about 100 prosecutors and law enforcement personnel in California. One of my themes was that there’s much more to personal safety and risk than bad guys with guns.

My presentation occurred a few months into the pandemic when threats against public officials at the local, state, and federal levels skyrocketed because of COVID-19 public safety measures. Many of these officials were assigned protective details. I suggested that these security teams need to know about and plan for their location’s natural hazards. Naturally, the same goes for emergency and business continuity planners, and others.

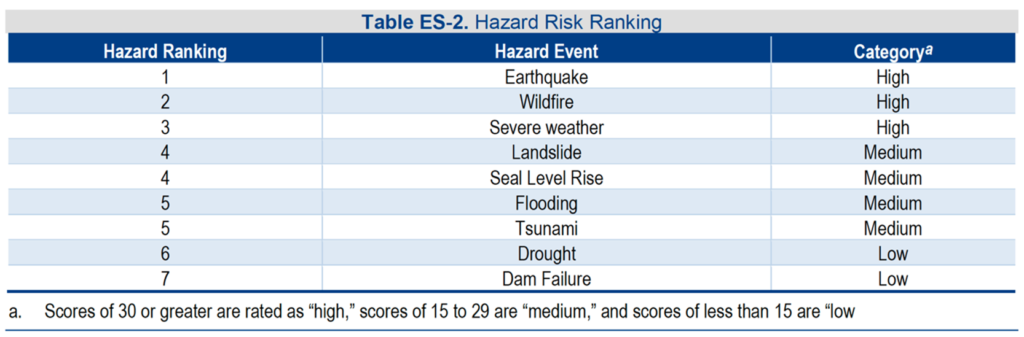

I used the example of Humboldt County, since that jurisdiction seemed to have the most representation in my audience. Located on California’s northern coast, the county is 225 miles north of San Francisco, the closest major metropolitan city. I noted that Humboldt County’s highest-ranking hazards, according to its Operational Area Hazard Mitigation Plan, are earthquakes, wildfire, and severe weather–in that order. Landslide, sea level rise, flooding, and tsunami aren’t far behind.

On December 20, 2022, a 6.4 earthquake struck Humboldt County. Two people died and 12 people were injured, according to the county. Over 70,000 people were left without power.

Disaster struck again shortly after that earthquake. Late December to mid-January was one of the wettest three-week periods in Northern California’s recorded history. It was the second-wettest three-week period in San Francisco’s (and probably the nine-county Bay Area’s) recorded history–only “The Great Flood of 1862”, which killed an estimated 4,000 people in January of that year, brought more rain. This latest bout of rain killed at least 21 people and caused damage in 41 of the state’s 58 counties.

Flooding is considered one of the three primary hazards in California (along with earthquake and wildfire), according to the state’s Hazard Mitigation Plan. In fact, the plan states “floods represent the second most destructive source of hazard, vulnerability, and risk, both in terms of recent state history and the probability of future destruction at greater magnitudes than previously recorded” (In its simplest form, risk is a factor of hazard and vulnerability).

But in a prime example of risk perception not reflecting risk reality, and as I mentioned in my previous newsletter, only 2% of homeowners in California have flood insurance (FEMA‘s flood risk maps do not help matters).

Hazard information is also available in countries to which you might travel for vacation, or countries in which your company is has established operations or is considering establishing operations. Company risk managers, business continuity planners, and security personnel should have this data, but much of it is open-source information available by internet search.

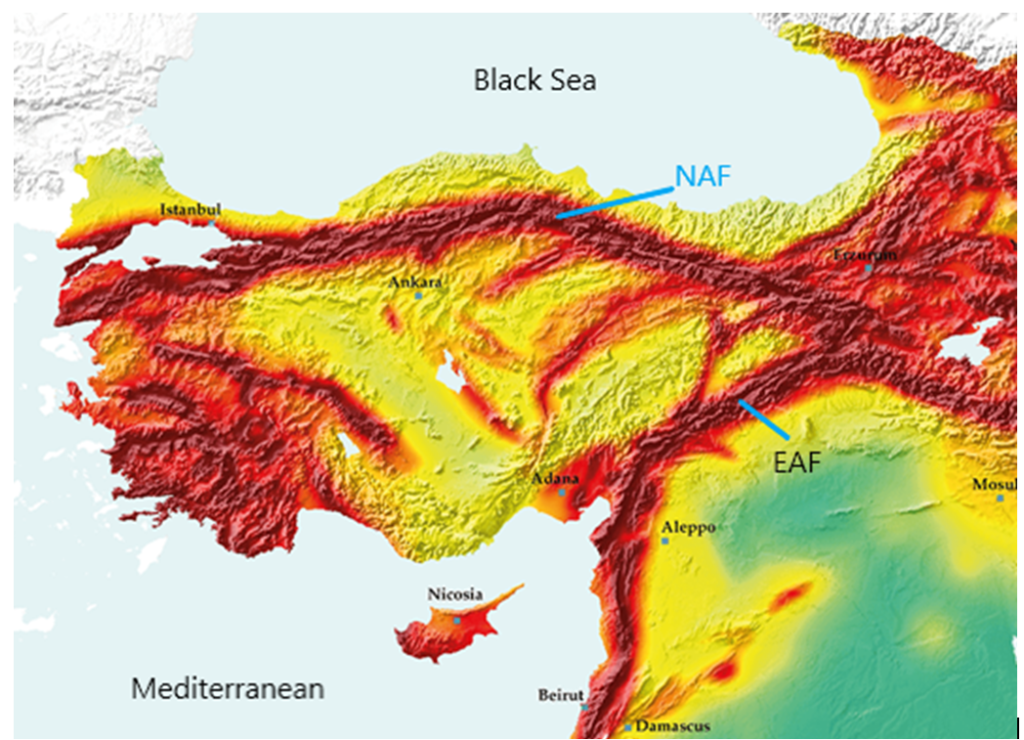

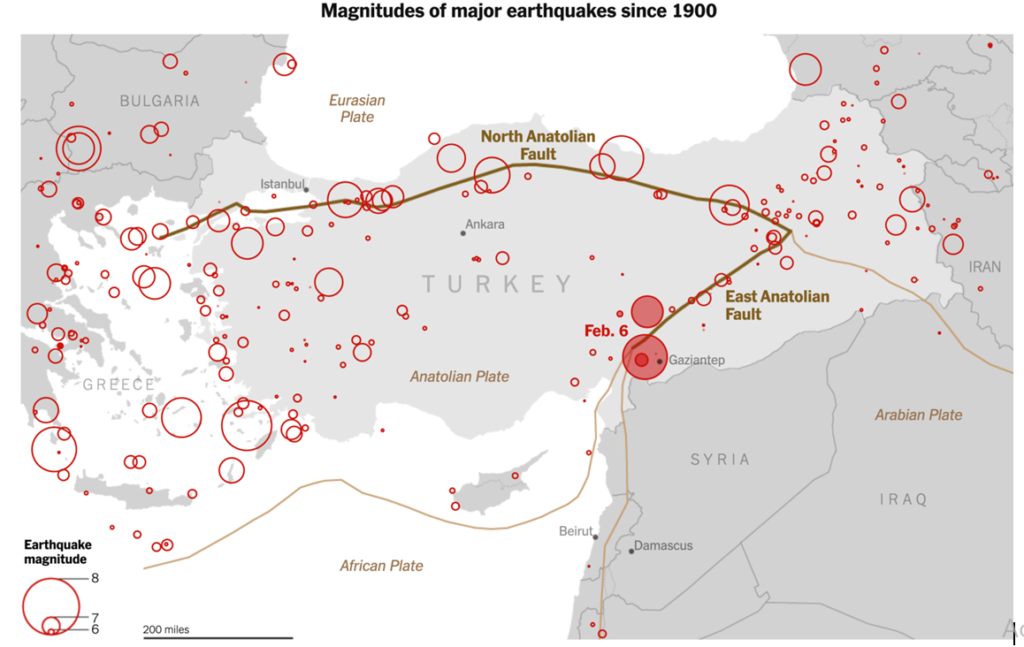

This 2016 article notes that bp, The Coca-Cola Company, GE, Procter & Gamble, Visa, and The Walt Disney Company have chosen Turkey as their “epicenter” (the article’s interesting word choice, not mine) in the region. In fact, Coca-Cola CCI, a multinational beverage company and one of the key bottlers for Coca-Cola, is headquartered in Istanbul. I assume (or hope) that these companies have planned for the fact that Turkey is one of the world’s most seismically active zones, and that in 1999 an earthquake just south of Istanbul (Turkey’s capital) killed 17,000 people and left 500,000 homeless. And that along with China and Iran, Turkey has had the most catastrophic earthquakes. It might also be safe to assume that these companies know that more than half of the buildings in Turkey do not meet earthquake building codes due to endemic corruption and a building code amnesty program (violators were allowed to pay a fine instead of bringing their buildings up to code).

In its 2021 annual report, CCI’s eight highest risk priority is “Natural Disaster & Business Continuity”, which it describes as “Adverse weather conditions, natural disasters, and public health crises may adversely affect our business, financial”. Although companies’ annual reports are not the place for risk minutiae, I am surprised by the lack of any specificity on Turkey’s geophysical hazards. After all, a bit more detail is provided for some of CCI’s other risks, such as supply chain interruptions & cost inflation, and cyber security. Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, has long been considered at risk for an earthquake due to its proximity to the North Anatolian Fault. This week the mayor of Istanbul warned that 90,000 buildings could collapse if a major earthquake were to hit the city. In 2021, 40% of CCI’s revenue and 32% of its EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization), a measure of profitability, came from within Turkey.

Kazakhstan, northeast of Turkey across the Caspian Sea, is also at high risk for earthquakes in the southern and eastern parts of the country. Citi, Deloitte, KPMG, McKinsey & Company, Microsoft, Nestlé Procter & Gamble, Philip Morris International, PwC, and Samsung Electronics are some of the multinational companies that have locations in Almaty, the country’s most populous city (two million people) and a major commercial and financial hub. IHG Hotels & Resorts, The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, L.L.C. and Rixos Hotels have hotels in Almaty. Almaty’s location on an active fault line, combined with shoddy building construction, could result in tens of thousands of deaths, similar to the deadly recipe that has led to almost 40,000 deaths in Turkey from its February 6 earthquake as of this writing. Kazakhstan’s last major earthquake occurred in 1911 and destroyed most of Almaty, killing over 400 people and destroying more than 600 houses along with 3,000 business premises, warehouses, and other non-residential buildings (landslides resulting from the earthquake caused many of the deaths and damage).

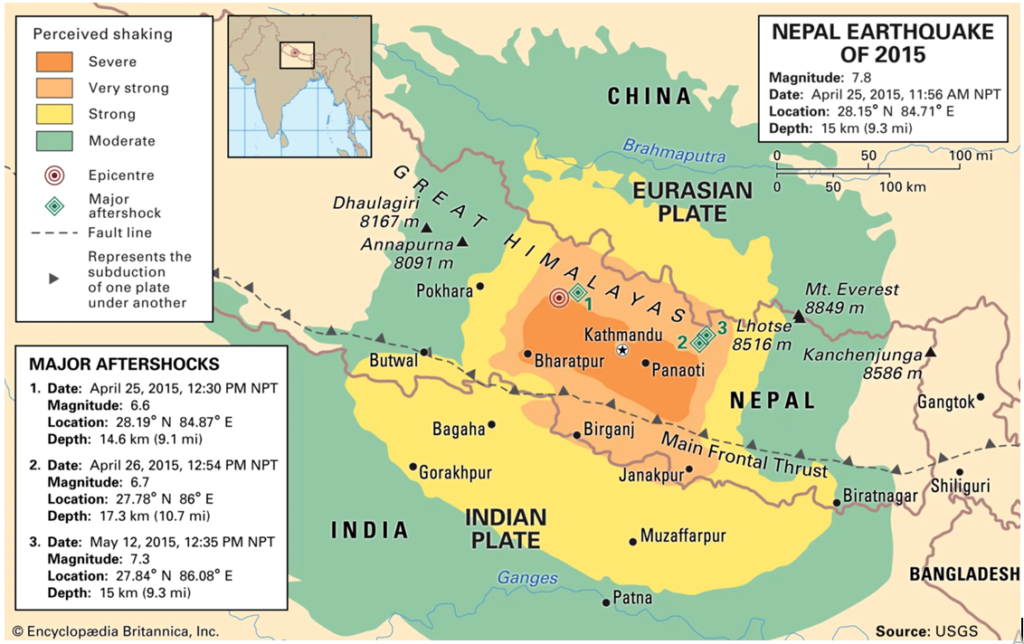

Nepal, about 1,000 miles (1,500 km) south of Kazakhstan, is another country that is seismically active but is also peppered with buildings vulnerable to tremors. In my military unit I mentioned in my previous newsletter, we assumed we would need to deploy to Nepal at some point to assist with the aftermath of an earthquake–the “Big Himalayan Quake”. We learned that the U.S. Marines stationed in the Pacific had even been exercising for that eventuality. Casualty estimates for this future earthquake were in the tens of thousands. Alas, the U.S. Secretary of Defense ordered our unit disbanded in 2011. Then in late-April 2015, the long-expected disaster hit Nepal. The 7.8 magnitude Gorkha Earthquake and a 7.3 magnitude aftershock in mid-May killed almost 9,000 people and destroyed or damaged 800,000 buildings and monuments. Reportedly 98% of deaths were because of falling buildings. Despite its destruction, some experts are unsure that the 2015 earthquake was actually the “Big Himalayan Quake”.

And there’s the circum-Pacific belt, also known as the “Ring of Fire”, a 25,000-mile (40,000 km) horseshoe-shaped belt of tectonic plate boundaries and undersea volcanoes. Roughly 90% of the world’s earthquakes occur in this region, which is also home to over 75% to 80% of the world’s active and dormant volcanoes. Densely populated, low-lying coastal communities within this Ring of Fire are at considerable risk.

- On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake (among the three largest earthquakes ever recorded) struck off the northeast coast of Honshu, Japan. It generated a tsunami with a maximum wave height of almost 130 feet (40 meters), which disabled the power supply and cooling of three Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors, causing a meltdown of their nuclear cores (a few members of my unit, including myself, were sent to Okinawa to help the Marines and U.S. State Department plan the worst-case evacuation of about 90,000 Americans and “designated foreign nationals” related to the nuclear accident). Almost 16,000 people died from the tsunami, which also caused 98% of the $220 billion USD in damage in the earthquake and tsunami disaster. This 2011 Great East Japan/Tohoku earthquake and tsunami is currently the most expensive natural disaster in history.

- On December 26, 2004, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake occurred off the northwest coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The Sumatra-Andaman Earthquake triggered a series of tsunamis that in totality were the deadliest and the most destructive in recorded history. The disaster affected over a dozen countries and claimed almost 230,000 lives, including over 167,000 in Indonesia and over 35,000 in Sri Lanka.

- In September 1992, an earthquake that caused little shaking on the earth’s surface triggered a deadly tsunami on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua. Waves reportedly reached almost 50 feet (15 meters) in some areas. The earthquake and tsunami killed at least 170 people and injured approximately 500. More than 13,500 were left homeless. The tsunami caused most of the damage.

Of course, flooding and earthquakes are only two types of hazard. And some natural hazards, like earthquakes, do not case direct harm to people. Their risk arises from the collapse of buildings and other man-made structures, and also from secondary hazards–such as when earthquakes cause landslides, soil liquefaction, or tsunamis. Sometimes the risk is from a combination of these structural vulnerabilities and secondary hazards, such as if an earthquake were to cause the collapse of a dam that subsequently leads to flooding.

Often, hazard-causing death, destruction, and individual and company losses result from vulnerabilities we create and don’t reduce/mitigate (e.g., urbanization on or near fault lines, and buildings not compliant with earthquake building codes) or the absence of risk transfer (e.g., lack of or insufficient insurance). The point is that for the vast majority of the world, experts know the risks associated with various local hazards. It is up to governments, individuals, and organizations to be knowledgeable about these risks and mitigate them when possible.